Introduction

Network: Connection between objects or a group of objects

Computer network: A set of communication elements connected by communication link.

Communication link:

-

Wired: Optical Fiber, Coaxial Fiber, Twisted pair cable.

-

Wireless: Radio wave, satellite connection, microwave.

Goals of Networks

- Efficient resource sharing

- Scalable

- Reliability

- Communication

- Application of Networks

- Remote data access.

- Remote software access.

- Emailing

- FIle transfer

Data communication

It is the exchange of data between two or more devices via some transmission medium

Components of Effective Data Communication

- Delivery: The data should be delivered to the destination it was intended to.

- Accuracy

- Timeliness

- Jitter free

Components of Data communication system

- Sender

- Receiver

- Message

- Protocols

- Communication/Transmission medium

Types of Communication

- Simplex: Unidirectional communication.

- Half Duplex: Bidirectional communication but only one direction at a time.

- Full Duplex: Two simplex connections in opposite directions.

Physical Structure

- Point to point

- Multipoint

Physical Topology

It tells how systems are physically connected through links. It is a geometric representation of the network.

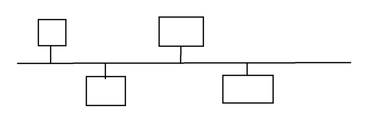

Bus Topology

Only one connection.

Advantages

- Easy to install

- Cheap

- Easy to expand

Disadvantages

- Only one device can transmit at a time, which makes it low speed.

- Single point of failure - faulty cable can bring down the whole system.

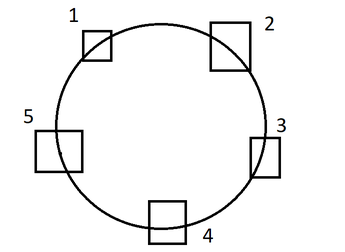

Ring Topology

Tokens are used to transfer data. Only one system can hold the token at a time. Token passing is done.

*Advantages

- Cheap

Disadvantages

- Not easy to install.

- Not easy to expand.

- If one system/one link goes down the entire ring will go down.

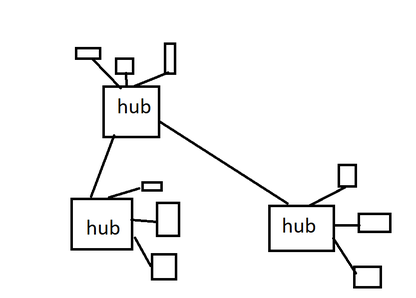

Star Topology

Uses a central hub.

_ Advantages and disadvantages same as of any centralized system_ Hub can also be expensive.

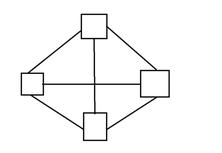

Mesh Topology

Advantages

- Less traffic

- No single point of failure

- Messages can be sent directly without any routing

Disadvantages

- Cabling cost will be higher

- Maintenance cost will be higher.

Tree Topology

Tree structure.

Networks Based on Geographical Area

- LAN - Local Area Network

- MAN - Metropolitan Area Network

- WAN - Wide Area Network

Differentiate based on cables, cost, etc.

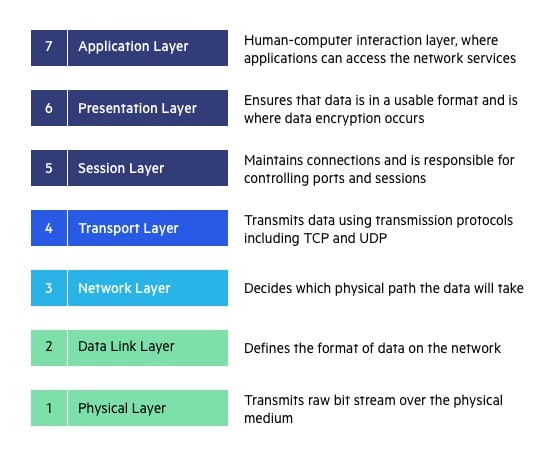

OSI Model - Open Systems Interconnection

Given by ISO.

The OSI model is a layered framework for the design of network systems that allows communication btw all types of computer systems.The purpose of OSI model is to facilitate communication btw different systems without requiring changes to the logic of underlying hardware and software.

Data in layers:

| S.No | Layer | Data | Responsibility | Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Application Layer | Data | To allow access to network resources | Telnet, SMTP,DNS, HTTP |

| 2 | Presentation Layer | Data | To translate, encrypt and process the data | |

| 3 | Session Layer | Data | To establish, manage and terminate session | |

| 4 | Transport Layer | Segment | Process to Process msg delivery, error recovery | TCP, UDP |

| (Port/Socket Address) | ||||

| 5 | Network Layer | Packet | Move packet from source to destination. | IP, ARP, RARP, ICMP |

| (Logical/IP Address) | ||||

| 6 | Data Link Layer | Frame | Hop to hop delivery, organize the frames | IEEE 802 Std., TR,PPP |

| (Physical/MAC Address) | ||||

| 7 | Physical Layer | Bit | Transmit bits over a medium, provide mechanical and electrical specification | Transmission media |

ARP - Address Resolution Protocol - Maps IP to MAC.

RARP - Reverse Address Resolution Protocol - Maps MAC to IP.

Physical Layer

It is responsible for moving physical bits. It defines:

- a transmission medium (wireless/wired)

- types of encoding to be used

- data rate

- synchronization of bits

- physical topology

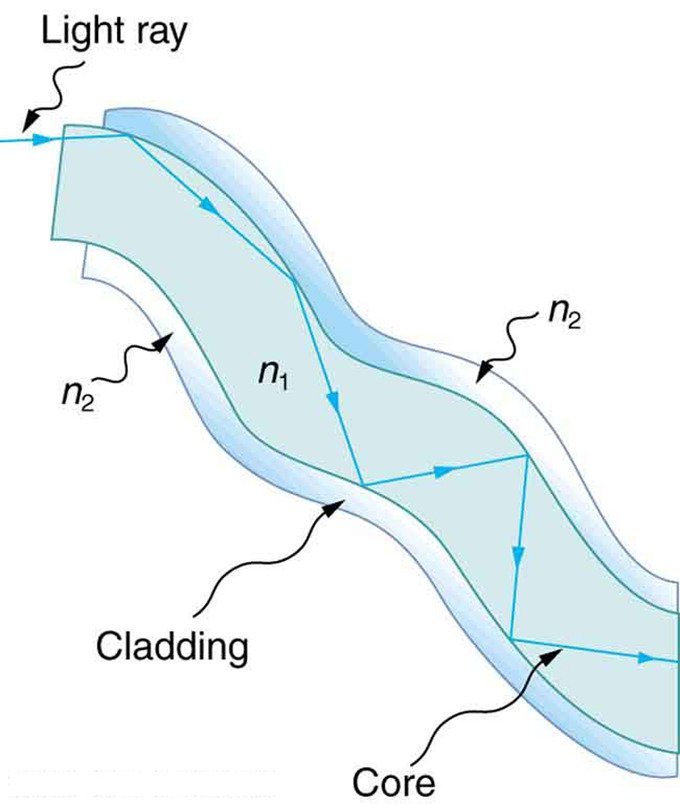

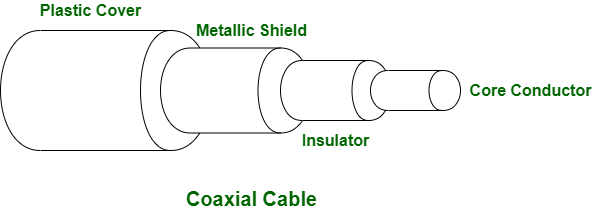

Transmission Media

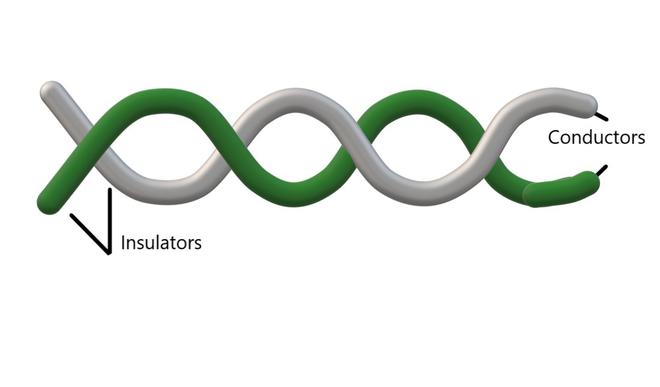

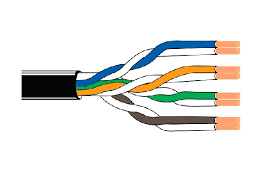

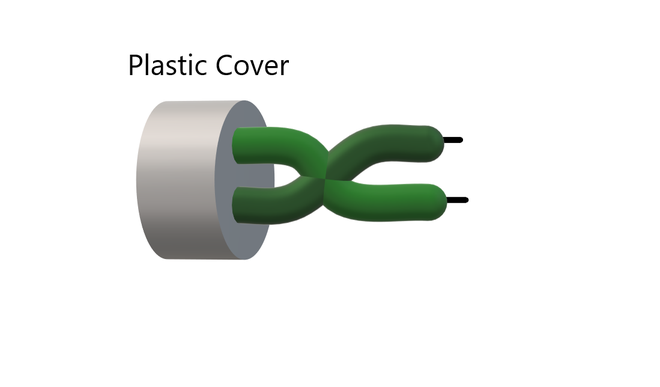

Wired/Guided Media:

-

Optical Fiber

-

Coaxial Fiber

-

Twisted pair cable

-

Unshielded Twisted Pair (USTC)

-

Shielded Twisted Pair (STC)

Wireless/Unguided Media:

Radio wave, microwave, and infrared

Electromagnetic Spectrum for Wireless Communication

- 3KHz - 300 GHz => Radio Waves and Microwaves

- 300Ghz - 400 THz => Infrared

- 400 THz - 900 Thz => Light waves (not used for transmission)

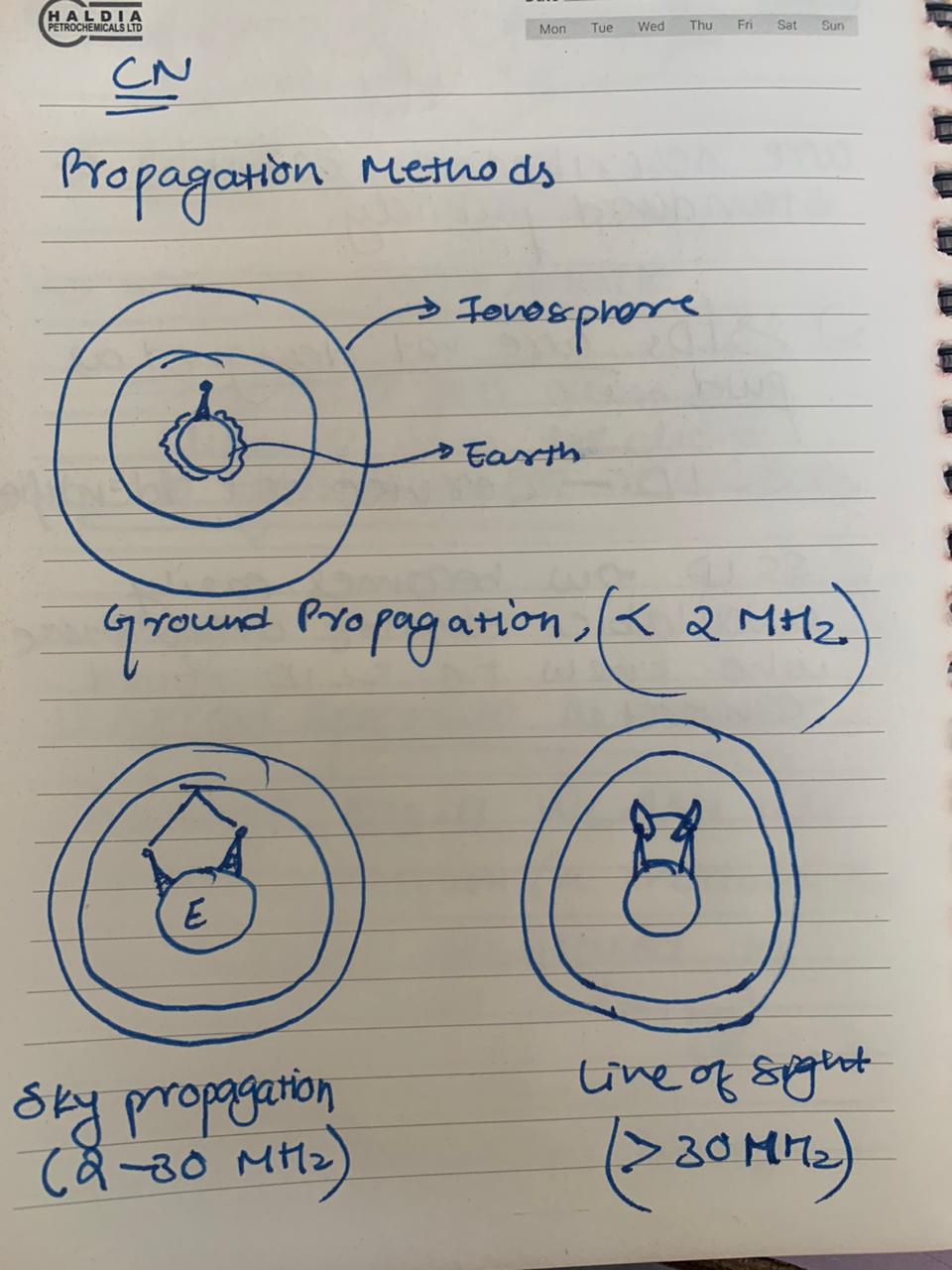

Propagation Methods

Ground, Sky, Line of Sight

Bands

| Band | Range | Propagation | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low Freq. | 3-30 KHz | Ground | Long range radio navigation |

| Low Freq. | 30-300KHz | Ground | Radio and Navigation Locator |

| Medium Freq. | 300KHz-3MHz | Sky | AM radio |

| High Freq | 3-30 MHz | Sky | Citizen Band(Ship/Aircraft Communication) |

| Very High Freq. | 30-300 MHz | Sky/Line of Sight | Cellular Phone, Satellite |

| Super high freq. | 3-30 GHz | Line of Sight | Satellite Communication |

| Extremely high freq. | 30-300 GHz | Line of Sight | Radar/Satellite Communication |

High Frequencies cannot travel through walls, lower frequencies can.

High Frequency have less distance, lower frequencies have higher distance.

Switched Networks

Large networks cannot have all nodes directly connected with each other. Therefore, to send data from one node to another, it has to be sent through other nodes.

Suppose there’s a network with many nodes, and node A wants to send some data to node B. There are two ways of doing so.

-

Packet Switching

Data is divided into small sized packets for transmission. This increased efficiency, reduces chances of lost data,etc.

1.Virtual Circuit - Source establishes a (virtual) path that the data will follow. Each packet goes through the same route.

- Datagram Switching - Source doesn’t decide any route. It sends each packet to the next nodes. Each node can decide where to forward the packets. Each packet may end up taking a different route. Packets may be delivered in a different order.

-

Circuit Switching

A special path is set up for the transmission, and the intermediate nodes are already decided before the data transmission takes place. There is a dedicated path set up for the transmission of that packet.

-

Message Switching - Entire message is transferred between nodes. Each node stores the message, then decides where to forward it. This is also called store and forward.

Network Architecture

Protocol is an agreement between two communicating parties on how the communication is to take place. Includes things like format of data, speed, etc.

Networks are organized as a stack of layers. Each layer offers its services to the layer above it (like OSI). Between each two layers there is an interface. Services are operations a layer provides to the layer above it. Protocols are used to implement services.

Set of layers and protocols is called the Network Architecture.

List of Protocols used by a certain system is called Protocol Stack. We generally have one protocol per layer.

Types of Communication on the basis of Connection

Connection-Oriented

- Similar to telephone.

- Establish a connection, communicate, and then release the connection.

Connectionless

- Like postal system

- Each packet has the destination address,

- Each packet is routed independently through the system.

TCP/IP Stack

Internet Protocol (IP)

- Hosts can inject packets into any network.

- They will travel to destination independently.

- They may arrive out of order.

- Connectionless.

- Similar to postal service.

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

- Transport Layer

- Source and Destination communicate using this.

- It is connection-oriented, reliable. Provides no-error delivery.

- Handles flow control

- Converts incoming byte-stream (continuous data like video or large amount of text) into discrete messages. Destination’s TCP reassembles them.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

- Transport Layer

- Connectionless, unreliable

- Faster than TCP.

Data Link Layer

Delay

Transmission Delay

The delay taken for the host to put the data onto the transmission line.

\[ T_t = L/B \]

where \(L\) is the size of the data, and \(B\) is the bandwidth.

Propagation Delay

Time taken by the last bit of the data to reach the destination (after it has been transmitted from host to transmission media at the source.)

\[ T_p = distance/velocity \]

Queueing Delay

Each packet waits in the buffer (at destination) before it is processed. The amount of time it waits is known as the queueing delay.

Processing Delay

This is the time taken to process the packet. Includes checking headers, updating TTL, deciding where to forward it,etc.

Queueing and Processing delays are generally taken to be zero, unless mentioned otherwise.

Framing Techniques

One of the major issue in framing is to decide how to specify the start and end of a frame.

One way to do this is to use fixed-size frames. For eg, if we say one frame is 50 bytes, then the destination’s data link layer will know that after the first 50 bytes, the next frame has begun.

This can lead to wastage of space. If the data in a frame is only 10 bytes, we have to add 40 bytes of empty space.

Thus variable-sized frames are more preferred.

Framing techniques for variable-sized frames are given below.

Character Count

It involves simply adding the number of characters in a frame to the data-link header. Before each frame starts, the number of characters in it is present.

For eg, we have 4 frames with lengths 3,4,2,5 characters respectively. Our data would look like:

(3)(frame1)(4)(frame2)(2)(frame3)(5)(frame4)

This isn’t used anymore, because a single bit error in the character

count could lead to miscalculation of frames. Count variable could also

only hold a certain limit of number. For e.g, if count was

specified as an 8-bit number, the maximum value it can hold is \(2^8-1 =

255\). If our frame has more than

255, we would face issues.

Hence this isn’t used.

Flag (Character Stuffing/Byte Stuffing)

We use a special flag byte at the start and end of each frame. It is fixed so it can be recognized.

An issue with this is that the flag byte may occur “accidentally” in the data itself. This may cause the DLL to assume the frame has ended even when it has not.

To solve this, we use a special ESC byte, which is also fixed. Accidental flag bytes have the ESC sequence inserted before them, to tell the DLL that this FLAG is data and not the end of a frame.

If ESC occurs within the data “accidentally”, we escape it with another ESC.

Examples

A Flag B –> A ESC Flag B

A ESC B –> A ESC ESC B

A ESC Flag B –> A ESC ESC ESC Flag B

A ESC ESC B –> A ESC ESC ESC ESC B

Doesn’t work if the data isn’t 8-bit.

Bit Stuffing

A special bit pattern denotes start and end of frames. Generally,

this is taken to be 01111110.

If the sender encounters the starting of this pattern in the data, it adds a 0 or a 1 before it ends so that the pattern never occurs. The receiver will do the opposite and remove the stuffed 0s or 1s.

For e.g, for 01111110,

If the sender encounters a 0 followed by 5 consecutive 1’s, it adds a

0 before continuing. This ensures that 01111110 never

occurs in the data.

The receiver will destuff these extra zeroes on its end.

01111110 –> 011111010

011011111111111111110010 –>

011011111011111011111010010

Error Detection and Control

Parity Check

Parity check is the simplest method of detecting errors. It involves using a single check bit after or before the frame.

We count the numbers of 1s and 0s in a particular frame. If it’s odd, check bit value is 1. If it’s even, check bit value is 0.

101011 - Check bit=0 101001 - Check bit=1

This can only detect single-bit errors. If two bits (a 0 and a 1) are flipped, the number of 1s remains the same. 2D parity check is more useful. The data is divided into rows and columns. Parity bit is calculated for each row and column.

1 0 1 0 1 | 1

1 1 0 0 0 | 0

1 0 1 1 0 | 1

_ _ _ _ _ |

1 1 0 1 1 | 0The final data becomes

101011

110000

101101

110110Hamming Code

Data - the original data to send

Redundant bits - bits that aren’t part of the original data. They have been added for error detection and correction.

Codeword - The final result that is sent to the receiver - combination of data and redundant bits.

Code is a collection of codewords.

Hamming Distance between two strings is the number of positions where the symbols are different. Only valid for strings of equal length. We will use it for binary numbers.

For eg, hamming distance btw 101 and 100 is 1 (only last bit is different) btw 101 and 110 is 2 (2nd and 3rd bits are different).

Hamming Distance of a Code is the minimum hamming distance between any two codewords in the code.

A code with a hamming distance of \(d\) can detect \(d-1\) bit errors, and correct \(\lfloor (d-1)/2 \rfloor\) errors.

For example, consider a code with the codewords 000 and

111. The hamming distance of such a code would be 3. We

should be able to detect 2-bit errors, and correct 1-bit errors.

Suppose we were transmitting the codeword 000 ande

during transmission bit flips occurred:

-

If the bit flip resulted in

001. We know this is not a valid codeword (only000and111are valid), so we know an error has occurred.The hamming distance between

111and001is 2.The hamming distance between

000and001is 1.Therefore, we can guess that the original word must have been

000. Similarly, we would be able to detect and correct errors if the bit flip resulted in010or100. -

If the bit flip resulted in

011(2-bit error).Once again we can see it isn’t a valid codeword, so we are able to detect the error.

But if we try correcting it, we would think that the original codeword was

111, since the hamming distance of (111,011) is less than that of (000,011). -

If the bit flip resulted in

111(3-bit error)We wouldn’t be able to detect the error, since

111is a valid codeword.

Thus we saw - we can detect 1-bit and 2-bit errors. We can only correct 1-bit errors.

Hamming Codes can also be used to detect and correct errors in a different manner.

Let’s say we have data of length \(m\). First we need to calculate the number of redundant bits needed to transmit this.

\[ m + r+1 \le 2^r \]

The smallest value of \(r\) satisfying this equation can be used as the number of redundant bits.

Format of the Codeword

- Total number of bits = \(n = m+r\).

- The bits at positions \(2^0, 2^1, 2^2, 2^3...\) and so on are check bits.

- The bits in the rest of the positions are data bits.

- Bits are numbered from 1.

Calculating the values of check bits

-

Suppose we have m=7. We can see that r=4 will work. Codeword length = 7+4=11.

-

Bits at positions 1,2,4,8 are check-bits.

-

Bits at positions 3,5,6,7,9,10,11 are data bits.

Suppose our data is 0100110 (7-bit) Final data will look like:

_ _ 0 _ 1 0 0 _ 1 1 0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Write the position number of data bits as sum of powers of 2.

3 = 1+2

5 = 1+4

6 = 2+4

7 = 1+2+4

9 = 1+8

10 = 2+8

11 = 1+2+8

To calculate value of check-bit 1:

- Check which equations have

1on the RHS. - Equations for bits 3,5,7 and 9 have

1on RHS. - So, we will do a parity count of bits 3,5,7,9

Bit 3 = 0

Bit 5 = 1

Bit 7 = 0

Bit 9 = 1

- Parity count = 0 (even number of 1’s). So, the value of check bit 1 is 0.

Value of check bit 2:

-

Equations for 3,6,7,10,11 have 2 on RHS.

-

Parity count:

Bit 3 -> 0

Bit 6 -> 0

Bit 7 -> 0

Bit 10 -> 1

Bit 11 -> 0

Parity Count = 1

-

Value of check bit 2 = 1

Similarly we can do for check-bit 4 and 8

Check bit 4:

Equations : 5,6,7 Parity check : 1,0,0 Parity count = 1

Value of check-bit 4=1

Check bit 8

Equations: 9,10,11 Parity Check: 1,1,0 Parity Count = 1

Value of check-bit 8 = 1

Final Codeword:

_ _ 0 _ 1 0 0 _ 1 1 0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

becomes

0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0Checksum

- Sum all the bits in the data word.

- If the checksum goes beyond n bits, add the extra leftmost bits to the n rightmost bits. (Wrapping)

- Take 1’s complement of the sum so found. This becomes our checksum

- Send the checksum along with the data to the receiver.

At receiver’s end: - Add all the data received (including the

checksum) - Perform wrapping if necessary. - The end result should be

1111....1, i.e, n times 1 - If the end result is anything

else, it means the data is wrong.

Example

Let n=4. We are sending 4-bit data.

Let the data be 4 numbers : 7,11,12,6.

- Add all the numbers: 7+11+12+6 = 36

- 36 cannot be represented in 4-bits, so we perform wrapping.

36 in binary 100100

Extra bits are the leftmost 2 bits (10)

Take them and add them to the rightmost 4 bits

0100

10

----

0110

----

Take 1's complement

1001

In decimal = 99 becomes our checksum which we send to the receiver.

At receiver’s end:

All the data is added.

7+11+12+6+9 = 45

45 cannot be represented in 4-bits, so we will do wrapping

45 in binary is 101101

Take extra digits - leftmost 2 (10)

Add to rightmost 4

1101

10

----

1111

----

We received the sum as 1111, so we know our data is correct.

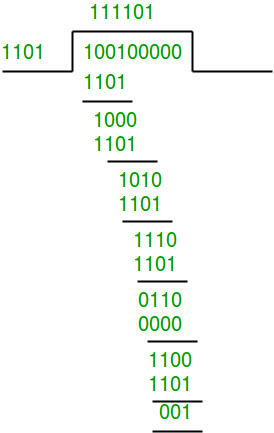

CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check)

Data - k-bit Codeword - n-bit Divisor - (n-k+1) bits. Divisor should be mutually agreed between sender and receiver.

- Add (n-k)

0s to the dataword. - Divide dataword by divisor using modulo-2 division.

- Append the remainder found to the original dataword (without the extra zeroes)

At receiver’s side:

- Perform modulo-2 division of the received code-word and divisor.

- If the remainder is 0, the data is correct. Otherwise it’s incorrect.

Modulo-2 Division

It’s a method of dividing 2 binary numbers.

It follows the rules and logic of normal division, with subtraction step replaced by bitwise XOR.

Flow Control

To make sure receiver receives all the data.

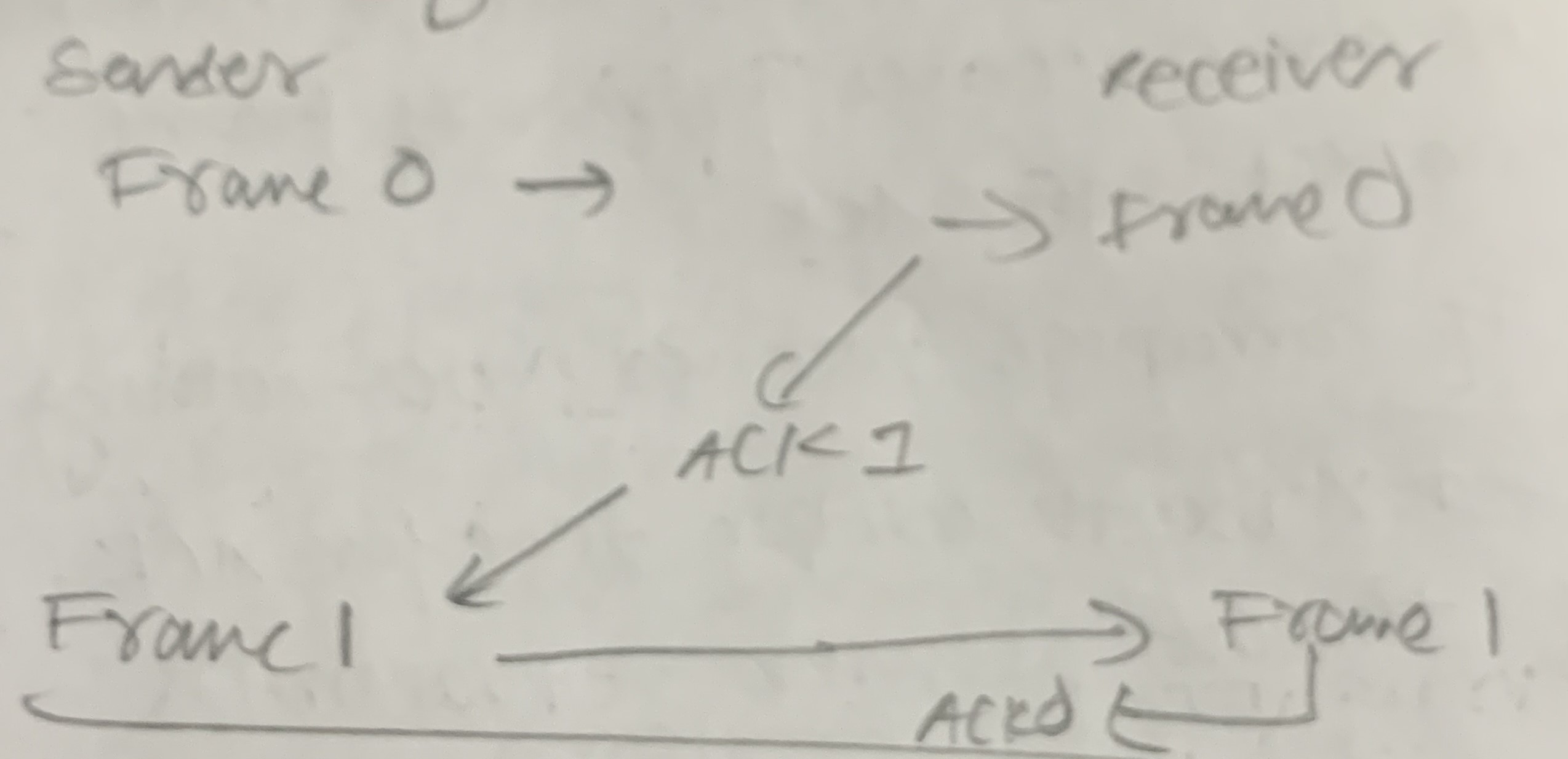

Stop & Wait ARQ (Automatic Repeat ReQuest)

-

Sender sends a frame and waits for ACK (acknowledgement) for the frame from receiver.

-

Receiver receives the frame. If the frame is correct, receiver sends ACK.

-

If the frame is corrupt, receiver drops the frame and does nothing.

-

Sender waits a certain amount of time for ACK from receiver. After this, it times out and resends the frame.

-

ACK message may also get lost, then the sender will assume the original frame was corrupted or lost. It will retransmit, which means the receiver may get duplicate data.

-

To avoid this, frames are numbered.

-

We only need to differentiate between a frame and its immediate successor. I.e, we need to differentiate between frame x and x+1. We don’t need to differentiate between frame x and x+2.

x+2 will never be sent unless both x and x+1 have been sent AND acknowledged.

-

Therefore, 1 bit sequence number is enough. If the first frame is 0, the second frame is 1, the third is again 0, and so on.

Formulas

Total time taken = Transmission time of data + transmission time of ACK + propagation time of data + propagation time of ACK + Queuing delay + Processing delay.

\[ = T_{t(data)} + T_{t(ACK)}+T_{P(data)}+T_{P(ACK)} +Delay_{Queue} + Delay_{Processing} \]

We take queue delay and processing delay to be 0. As ACK is very small, we take transmission time of ACK to be 0.

\[ = T_{t(data)} + T_{P(data)}+T_{P(ACK)} \]

Propagation time of ACK and data will be same.

Total time = \(T_t + 2*T_p\)

Where \(T_t\) is transmission time of data, and \(T_p\) is propagation time.

Efficiency = \(\eta\) = Useful Time/ Total Time

\[ = \frac{T_t}{T_t+2*T_p} \] \[ = \frac{1}{1+2(\frac{T_p}{T_t})} \] \[ = \frac{1}{1+2a} \]

where a = \(T_p/T_t\).

Throughput = \(\eta\) * Bandwidth

Go Back N

- Sliding Window Protocol

- Receiver window Size = 1

- Sender Window Size = \(2^m-1\)

- Sequence numbers for frames – \([0,1,....2^m-1]\), 0 and \(2^m-1\) inclusive.

- Window Size = WS/W

- We send up to W frames at a time, and keep them in memory until the receiver ACKs them.

- Receiver only receives one frame at a time.

- Receiver can send a single ACK for many frames. For eg if sender sent 7,8,9 and receiver received all, it can simply send ACK 10.

- If receiver receives wrong frame (e.g receiver was waiting for frame 3 and frame 4 came), or a corrupted frame, it stays silent.

- Sender’s timer will timeout. Sender will resend all frames in the window.

For e.g, if WS=3 and sender has sent 1,2,3,4,5,6 and timer for 3 times out (1 and 2 ACKed successfully), sender will send 3,4,5 again.

Efficiency = \(\eta = \frac{WS}{1+2a}\)

where \(a=T_p/T_t\)

For maximum efficiency (100% usage),

-

WS = 1+2a

-

No. of bits needed for sequence number = \(\lceil log(1+2a) \rceil\)

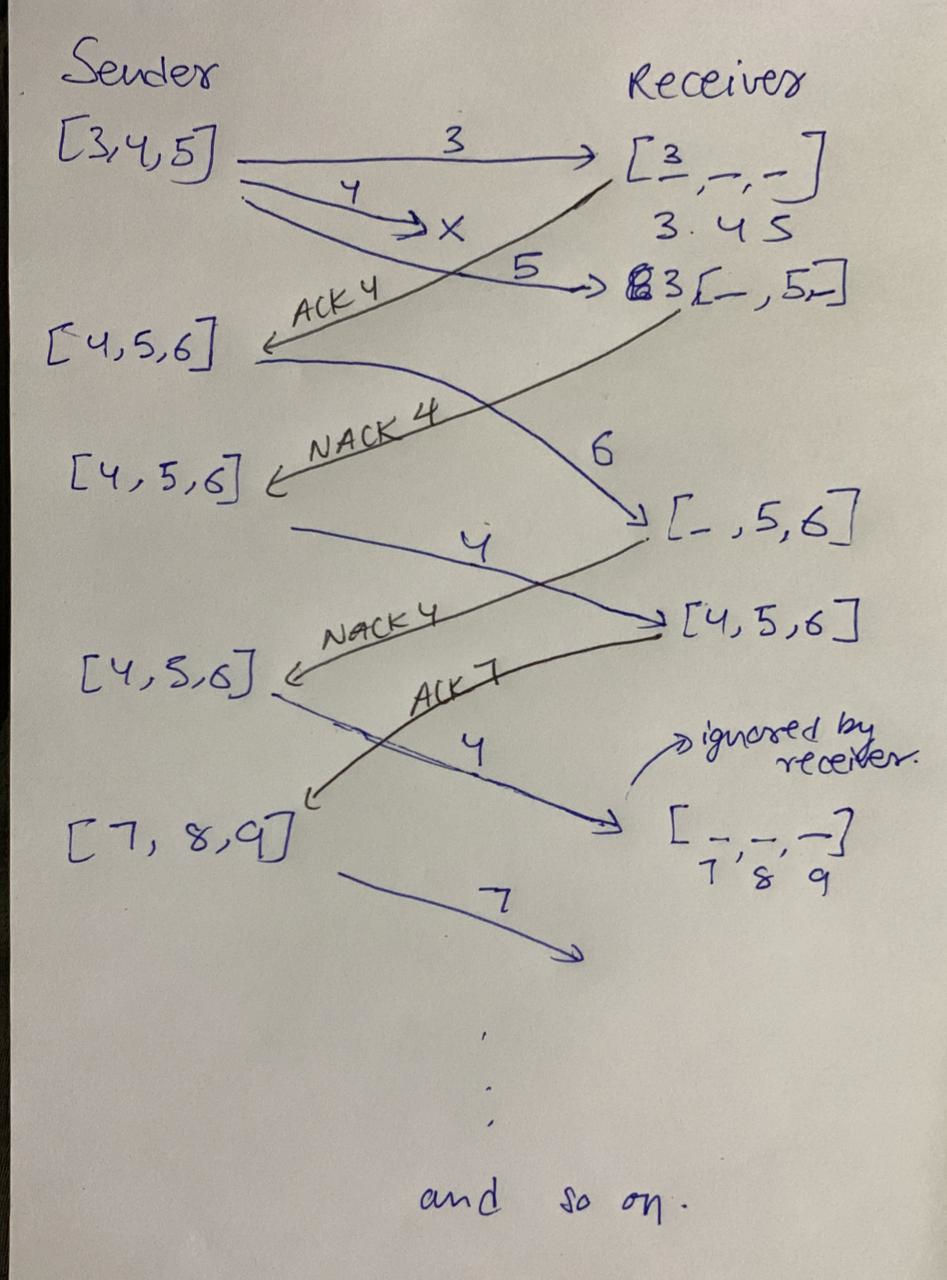

Selective Repeat (SR)

-

Only lost/corrupted frames are resent.

-

Sender window size = Receiver Window Size

-

Window Size = \(2^m/2\)

-

Receiver buffers frames that are within its window range. Others are dropped. For e.g, if receiver’s window is waiting for frames 3,4,5 and sender sends 6, it will be dropped.

-

ACK is only sent after frames are received in order. If receiver window is 3,4,5 and we receive 4,5 - 4,5 will be stored and buffered, but no ACK will be sent.

Instead, receiver will send a negative acknowledgement (NACK) for 3 - NACK 3.

-

This tells the sender that receiver hasn’t received 3.

-

Sender will resend 3 (only 3).

-

When 3 is received, receiver will send ACK 6.

-

If we had received 3 in the beginning, we would have immediately sent ACK 4. This would also make the receiver move its window to 4,5,6.

Example case:

- Sender window = [3,4,5],6,7. Sender sends 3,4,5.

- Receiver receives 3 and sends ACK 4. 4 is lost. Receiver buffers 5 and sends NACK 4. Receiver moves its window by 1 to [4,5,6],7.

- As soon as the sender receives ACK 4, it knows receiver has received 3.

- It will move its window by 1 to [4,5,6],7. As 5 has already been sent, sender will now also send 6.

- Sender will receive NACK 4 and resend 4.

- Receiver will receive 6 from sender, and buffer it. Receiver still hasn’t received 4. It will send NACK 4.

- Receiver will receive 4 from sender. It has 5,6 so it will send ACK 7.

- Sender will receive the second NACK and again send 4

- Receiver will receive the 4 (that the sender sent earlier), and accept it. 4,5,6 have all been received. Receiver will send ACK 7, and move its window to [7,8,9]

- Receiver will receive the second 4 sent by the sender. It will be ignored since it’s out of the window.

- Sender will receive ACK 7 and move its window to [7,8,9].

- Transmission will continue as normal from here.

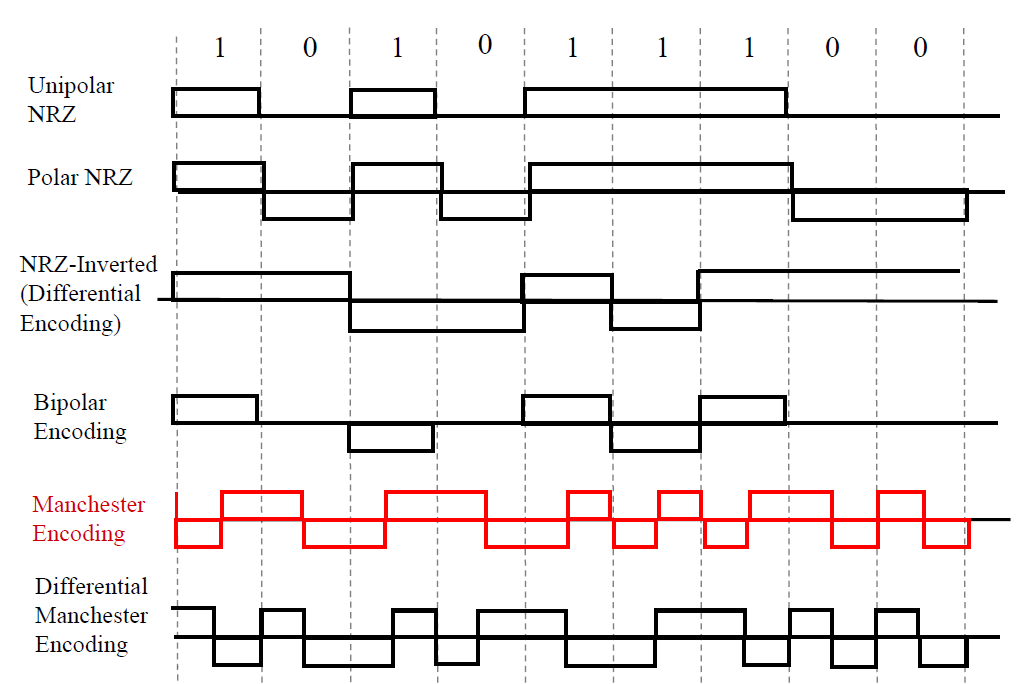

Data Encoding Techniques

NRZ-Unipolar

1 - +ve

0 - 0

NRZ-Polar

1 - +ve

0 - -ve

NRZ-I

Differential Encoding.

1 - Signal transition at start (high-to-low or low-to-high)

0 - No signal transition at start

Manchester

Always has a mid-bit transition:

1 - Low to High

0 - High to Low

The start of the bit may also have a transition, if needed according to the bit’s value.

For eg, if the bit is 1 (which means we need a low to high transition in the middle), and the interval starts with a high value, we will transition to low at the start.

(Eg - Encoding 11)

Differential Manchester

Mid-bit transition is only for clocking purposes.

1 - Absence of transition at the start.

0 - Presence of transition at the start.

Bipolar Encoding

1 - Alternating +1/2, -1/2 voltages

0 - 0 voltages

Media Access Sublayer

The data link layer is divided into two sublayers.

- Media Access Control (MAC) - Defines the access method for each LAN.

- Logical Link Control (LLC) - Flow control, Error control, etc.

Framing is handled by both.

Media Access Control and Multiple Access Protocols

Handle how multiple nodes can communicate on a single link.

Random Access/ Contention Methods

- All nodes are considered equal.

- No scheduled transmission.

- Transmission occurs randomly.

- Nodes compete for access.

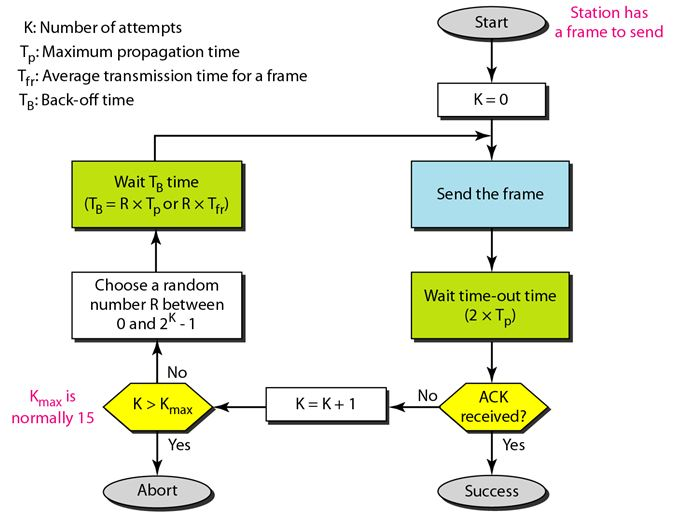

Pure Aloha

-

Each node sends a frame when it has a frame to send.

-

Obviously, we will have collisions in case 2 nodes decide to send a frame together.

-

Aloha expects the receiver of the frame to send ACK for the frame.

-

Vulnerable time for Aloha is \(2*T_t\). This is the time frame in which collisions can happen.

For eg, A sent a frame at 12:05

Let transmission time = 5 minutes.

B wants to send a frame. But it cannot send a frame until 12:10, because till 12:10 A will be transmitting its frame. A collision will occur if B sends before 12:10.

Similarly, if C had earlier sent a frame anytime after 12:00, A’s frame will collide with it.

Therefore, the vulnerable time is 12:00 - 12:10, which is 10 minutes = twice of transmission time.

-

In case a collision occurs, the node waits a random amount of time before retransmitting. How much time to wait is explained in the flowchart below.

-

Maximum number of attempts are fixed.This value is called \(K_{max}\) For eg, if max attempts = 15, if a node has transmitted the same frame 15 times and always gotten collision, it will abort and try again some time later.

-

\(K_{max}\) is generally set to be 15.

Efficiency of Pure Aloha \[ S = G.e^{-2G} \]

where \(G\) is the the average number of frames created by the entire system (all nodes combined), during the transition time of a single frame.

For eg, if \(T_t\) is 1ms, G is number of frames produced per millisecond.

\(S_{max}=0.184\) at \(G=1/2\).

The procedure of choosing a random number between 0 and \(2^K-1\), incrementing the value of K, and waiting an amount of time based on R, is called the backoff procedure.

Slotted Aloha

- Same as Aloha, but time is divided into slots.

- Time is discrete and globally synced (all nodes have same value of time)

- Frames can be sent only at the beginning of a time slot.

- Vulnerable Time = \(T_t\)

Efficiency of Slotted Aloha \[ S = G.e^{-G} \]

\(S_{max}=0.368\) at \(G=1\).

CSMA (Carrier Sense Multiple Access)

- Each node will sense the medium before sending.

- If the medium is idle, send the data. Otherwise wait.

- Collisions may still occur due to propagation delay.

For e.g, if A sent a frame at 12:01, and propagation time from A to D is 2 minutes. If D checks the medium at 12:02, it will find it idle and send the frame. A’s frame and D’s frame will then collide.

- Vulnerable time = \(T_p\) (Max propagation time).

Persistence Methods for CSMA

Persistence methods decide when and how to send data after sensing medium.

1-Persistent

- Continuously Sense the medium.

- As soon as the medium is idle, send the data immediately.

Non-Persistent

- If medium is idle, send the data immediately.

- If medium busy, wait a random amount of time, then sense the medium again and repeat from step 1.

- Less efficient, as the channel may remain idle in the random waiting time.

- Less chance of collision.

P-Persistent

Uses a value \(p\) that is fixed by the network administrator for each node. Different nodes have different values of \(p\) 1. Continuously check medium till idle. 2. If idle: - Generate random number \(r\) - If \(r<p\), then transmit the data. - Else: - Wait for a time slot, and then check the line. - If line is idle, go to step 2. - If the line is busy, act as if a collision occurred, and follow the backoff procedure.

CSMA with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD)

- Continue sensing medium for time= \(2*T_p\) after transmission.

- This will help us sense potential collisions.

- If a collision is detected, the node that detected the collision will send a jamming signal to the access medium. After that, backoff procedure will be applied.

- Condition to detect collision: \[ T_t=2*T_p \] The transmission time for the frame should be long enough that we can detect collisions while we are transmitting it.

- Efficiency of CSMA/CD is\[\eta = \frac{1}{1+6.44a}\] where \(a=T_p/T_t\).

Network Layer

- Moves packet from source to destination

- Uses routers, bridges, switches.

- Deals with IP addresses.

Performs the following functions:

- Routing

- Fragmentation

- Congestion Control

IP addresses have two parts - network ID, and host ID. Network ID represents which network the IP address is part of, i.e, which organization controls it. Host ID represents which computer (or mobile,printer,etc.) in that network the IP address belongs to.

For e.g, Google has many servers. They will all have the same Network ID, but different Host IDs.

Classful Addressing

IPv4 addresses were divided into various classes for easier addressing purposes.

An IPv4 address is a 32-bit address. For ease of representation, it is divided into 4 octets. Each octet contains 8-bits.

(8)(8)(8)(8)

It allows us to write the IP address in the following format - 192.168.10.1 Here, 192 is the first octet, 168 is the second, and so on. All are represented in decimal. This is called Dotted Decimal Representation.

Class A

In this, the first bit of the first octet is always fixed as 0.

0 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ . (octet 2) . (octet 3) . (octet 4)The range of the first octet becomes 00000000 to

01111111, i.e. 0 to 127.

The 1st octet represents the Network ID (7-bits).

The 2nd, 3rd and 4th octet represent the Host ID (24-bits).

Number of IP Addresses in Class A = \(2^{31}\), which is half of all IPv4 Addresses in the world.

Total number of Networks = \(2^7-2 = 126\). Range is [1,126].

The network IDs 00000000 and 01111111 are reserved and unused. They aren’t given to any organization.

Total number of hosts in each Network = \(2^{24}-2\)

Host with values 0.0.0 and 255.255.255 (first and last hosts) are also reserved and unused.

The host with value 0.0.0 is used to represent the entire network. So, for a network with networkID = 28, 28.0.0.0 is used to represent the entire network (and not any particular host in the network).

Host with value 255.255.255 is used to represent Direct Broadcast Address. If anyone wants to send a particular message to all the hosts in a network, they will use this. For a network with networkID =28, 28.255.255.255 represents its direct broadcast address.

Default Mask for class A is 255.0.0.0

For any IP address, performing bitwise AND of the IP Address, and the Default Mask for its class will give us the network that IP address belongs to.

For eg, let the IP address be 28.12.34.1

First bit of first octet is 0, so we know it’s a class A Address.

Bitwise AND with 255.0.0.0

00011100.00001100.00100010.00000001 (28.12.34.1)

11111111.00000000.00000000.00000000

-----------------------------------

00011100.00000000.00000000.00000000

= 28.0.0.028.0.0.0 represents the network that the IP address 28.12.34.1 belongs to.

Class B

First octet has first 2 bits fixed as 10

1 0 _ _ _ _ _ _ . (octet 2) . (octet 3) . (octet 4)First 2 octets represent the Network ID.

Last 2 octets represent the Host ID.

Range is (128-191)

Number of IP Addresses = \(2^{30}\), 25% of all IPv4 addresses in the world.

Number of networks = \(2^{14}\)

Number of hosts in each network = \(2^{16}-2 = 65534\)

First and last hosts are excluded here, as they were in class A.

Class A excluded first and last networks also. Class B excludes first and last hosts only. All networks in Class B are available for use.

Default Mask - 255.255.0.0.

Class C

First octet has first 3 bits fixed as 110

1 1 0 _ _ _ _ _ . (octet 2) . (octet 3) . (octet 4)First 3 octets represent the Network ID.

Last octet represent the Host ID.

Range is (192-223)

Number of IP Addresses = \(2^{29}\), 12.5% of all IPv4 addresses in the world.

Number of networks = \(2^{21}\)

Number of hosts in each network = \(2^8-2 = 254\)

First and last hosts are excluded here, as they were in class A.

Class A excluded first and last networks also. Class C excludes first and last hosts only. All networks in Class C are available for use.

Default Mask - 255.255.255.0.

Class D

First Octet has first 4 bits reserved as 1110

1 1 1 0 _ _ _ _ . (octet 2) . (octet 3) . (octet 4)Range is (224-239)

Number of IP Addresses = \(2^{28}\)

In class D, all IP addresses are reserved. There is no network ID and no host ID.

These IP addresses are only meant to be used for multicasting, group email, broadcasting, etc.

Class E

First Octet has first 4 bits reserved as 1111

1 1 1 1 _ _ _ _ . (octet 2) . (octet 3) . (octet 4)Range is (240-255)

Number of IP Addresses = \(2^{28}\)

All IP addresses are reserved for military purposes.

Classless Addressing

This divides 32-bit IP addresses into BlockID and HostID.

BlockID is similar to NetworkID.

Format - x.y.z.w/n

\(n\) represents the number of bits used to represent the blockID.

It also represents the number of 1-bits that the mask for this IP address should have.

For e.g - 128.225.1.1/10

This means the first 10 bits represent the block ID, and rest 22 bits specify host ID.

The mask for this network would be -

11111111.11000000.00000000.00000000, (10 times 1, then all

0)

To find the network, we do bitwise AND of IP address and mask

10000000.11100001.00000001.00000001

11111111.11000000.00000000.00000000

-----------------------------------

10000000.11000000.00000000.00000000

= 128.192.0.0The network that IP address belongs to is 128.192.0.0/10

Rules for Classless Addressing

-

Addresses should be contiguous

-

Number of addresses must be in power of 2.

-

1st address of every block must be evenly divisible by block size (number of hosts)

Block Size = number of hosts = \(2^{32-10}=2^22\) First address of block is same as network’s IP address = 128.192.0.0/10 = 10000000.11000000.00000000.00000000 = 10000000110000000000000000000000

We don’t need to divide. We can just check that the last 22 (22 is number of bits used to specify host) bits are 0.

i.e, the 22 least significant bits (LSBs) should be 0, which is true in our case.

Subnetting

Subnetting is the process of dividing a large network into smaller subnets. This helps in organization, security, fixing bugs, etc.

An organization may divide it’s network into separate subnets for finance department, legal department, etc.

We do this by dividing the hosts.

NetworkID REMAINS UNCHANGED IN SUBNETTING, ALWAYS.

Subnetting in Classful Addressing

Suppose we have a network with the IP 200.10.20.0. This

is a Class C IP address.

It has a total of 254 hosts. We want to divide it into 2 equal subnets.

- Network ID is 200.10.20. This will remain unchanged.

- The last octet is used to specify the host. Let’s say we want 2 subnets - \(S_1\) and \(S_2\).

- We will subnet by fixing the first bit in the last octet as either 1 or 0.

\(S_1\)

For the last octet, we will prefix the first bit for \(S_1\) as

1.

\(S_1\) will have IP addresses of

the form 200.10.20.1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _.

Range => 200.10.20.128 - 200.10.20.255

Usable IP addresses = \(2^7-2 = 126\)

Network IP address for \(S_1\) is 200.10.20.128.

Broadcast IP address is 200.10.20.255

\(S_2\)

For the last octet, we will prefix the first bit for \(S_2\) as

0.

\(S_2\) will have IP addresses of

the form 200.10.20.0 _ _ _ _ _ _ _.

Range => 200.10.20.0 - 200.10.20.127

Usable IP addresses = \(2^7-2 = 126\)

Network IP address for \(S_1\) is 200.10.20.0.

Broadcast IP address is 200.10.20.127

Thus, if the network receives a packet meant for 200.10.20.50, it will be sent to \(S_2\).

A packet meant for 200.10.20.165 will be sent to \(S_1\).

Subnet Mask

Since we are indirectly using 1 extra bit to specify Network ID now, our subnet mask will also have 1 extra bit added to it.

Class C’s Subnet mask is 255.255.255.0

Now, it will be 255.255.255.1 _ _ _ _ _ _ _.

We added 1 in the place where we prefixed an extra bit.

Subnet mask for our network is now 255.255.255.128

Our total number of usable IP addresses has become 126+126= 252. Earlier, it was 254.

Due to subnetting, we have lost the use of 2 IP addresses.

Number of usable IP addresses = Number Of Original Usable IP Addresses - \(n*2\)

where \(n\) is the number of subnets.

Subnetting in Classless Addressing

The procedure is mostly the same as for subnetting in classful addressing. The only extra thing that needs to be done is to change the value of \(n\).

For.eg,

128.192.0.0/10 - let this be our network.

First 10 bits specify block. Last 22 bits specify host.

10000000.11000000.00000000.00000000. The bold part represents block ID.

To subnet into two equal subnets, we fix the first host-bit.

Subnet 1 will have IP addresses of the form 10000000.1110_ _ _ _ ._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _. (We prefixed 0)

Subnet 2 will have IP addresses of the form 10000000.1111_ _ _ _ ._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _. (We prefixed 1)

To find out IP Addresses for Subnet1 and Subnet2, we will have to increase the value of \(n\) by 1, since now we are using an extra bit to find out block ID.

Subnet1 IP Address = 128.192.0.0/11

Subnet2 IP Address = 128.224.0.0/11

Accordingly, mask will be changed.

Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM)

In case we want subnets of different sizes, we use this technique. It works for both classless and classful addressing in similar ways. We’ll explain using classful here.

Suppose we have a network with IP 200.10.20.0.

We want to divide it into 3 networks - \(S_1,S_2,S_3\). \(S_1\) should have 50% of all hosts. \(S_2\) and \(S_3\) should have 25% each.

We will subnet in the following way:

\(S_1\)

IP Addresses of the form - 200.10.20.0 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ (1 bit prefixed)

Range - 200.10.20.0 - 200.10.20.127

Usable IP Addresses - 126

\(S_2\)

IP Addresses of the form - 200.10.20.1 0 _ _ _ _ _ _ (2 bits prefixed)

Range - 200.10.20.128 - 200.10.20.191

Usable IP Addresses - 62

\(S_3\)

IP Addresses of the form - 200.10.20.1 1 _ _ _ _ _ _ (2 bits prefixed)

Range - 200.10.20.192 - 200.10.20.255

Usable IP Addresses - 62

For \(S_1\), we prefixed only 1 bit. For \(S_2\) and \(S_3\) we prefixed two bits. We can see that the \(S_1\) has roughly double the number of IP addresses that \(S_2\) and \(S_3\) each have.

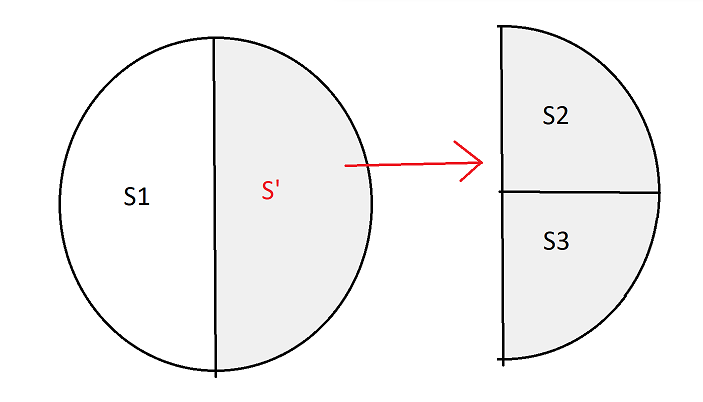

We divided the network into two equal halves - \(S_1\), and let’s call the other part \(S'\).

Then, we further divided \(S'\) into \(S_2\) and \(S_3\).

Header Formats for IP Protocols

Whenever a packet is sent using IP (IPv4 or IPv6), it includes data (payload), as well as a header. The header doesn’t contain the actual data, but it contains metadata such as destination, priority, source, etc.

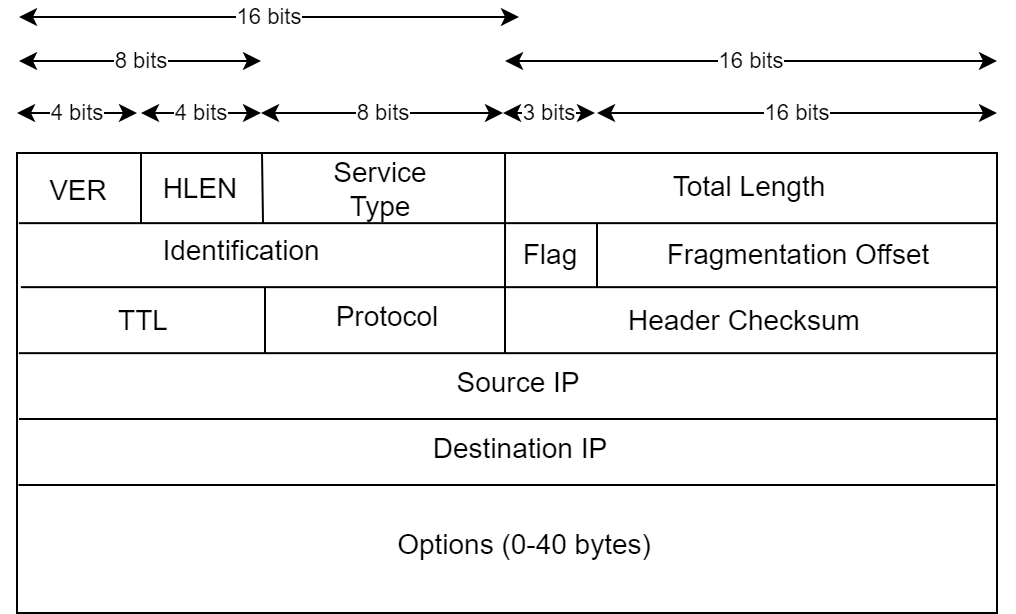

IPv4 Header Format

- IPv4 is a connectionless datagram service.

- Header size is between 20-60 bytes.

- The total datagram size is at max 64 KB, or 65535 bytes.

- The payload size is maximum 65515 bytes. This happens when the header size is 20 bytes. In case the header size is larger than 20, the max payload size will be decreased accordingly.

VER

-

Stands for version. It is a 4-bit value. It contains the value of version, i.e, which IP version is being used.

-

Almost all transmissions either use IPv4 or IPv6.

-

Version for IPv4 is 4 = 0100

-

Version for IPv6 is 6 = 0110

HLEN

- Contains the header-length.

- 4-bit value.

- Uses a factor of 4.

Header size = HLEN*4.

As the minimum header size for IPv4 is 20 bytes, HLEN can never be 0,1,2,3 or 4.

Type of Service

- Also known as DSCP (Differentiated Service Code Point)

- 8-bit value

- Contains different values specifying the type of service we wish to use.

The 8 bits are:

[P][P][P][D][T][R][C][0]

The first 3 bits (P) are used to set the precedence, or priority of the packet.

D - Delay.

0 means normal delay. 1 tells router this packet needs minimal delay.

T- Throughput

0 - normal

1 - maximize

R - Reliability

0 - normal

1 - maximize

C - Cost

0 - normal

1 - minimize

The last value is reserved as 0. It’s fixed for future use. Only one bit out of D,T,R and C can be 1 in a packet. More than 1 cannot be 1. For eg - 0011 is not valid.

Total Length

Contains total length of the packet. 16-bit value.

TTL (Time to Live)

- 8-bit value

- Source sets it to max value (255), or it can also be set as (max number of routers between source and destination)*2.

- At each node it encounters (router/switch/etc.), the value is reduced by 1.

- When it becomes 0, the packet is dropped.

- This helps in case a packet is getting stuck in loops in the network, causing congestion.

Protocol

- 8-bit

- Tells which protocol is being used, TCP,UDP, etc.

Header Checksum

- Contains the checksum value for the header.

- 16-bit

- Only IP header fields are used while calculating checksum, actual data isn’t used. This is because higher level protocols such as TCP and UDP use their own checksums for the data, so it isn’t required for IP to do it as well.

- Since fields like TTL can change, header checksum is recalculated at each router.

Source IP

- Contains IP address of the source

- 32-bit

Destination IP

- Contains IP address of destination.

- 32-bit

Fragmentation is done for packets that are larger in size than the permitted size.

The packet is broken down into many smaller packets, then sent over the network. It is reassembled at the source.

The IPv4 header contains values to identify the fragments.

Identification Bits

This is a 16-bit unique packet ID. It identifies a group of fragments that belong to a single IP datagram.

Flag

3-bit value.

[R][D][M]

The first bit is reserved as 0.

The second bit (D) stands for Do not Fragment. If this bit is 1, no node will try to fragment this bit. But, if some node doesn’t allow a packet of a large size, and we set D=1, the node may drop that packet altogether.

The third bit (M) stands for More Fragments

If M=0, either this packet is the last packet in its datagram, ot it’s the only fragment.

If M=1, it means more fragments are coming after this packet.

Fragment Offset

This represents the number of data bytes ahead of this particular fragment, i.e, the position of this fragment in the original unfragmented datagram.

It uses a factor of 8.

I.e, number of bytes ahead = Fragment Offset * 8.

For eg, if a datagram is broken into 4 fragments of 80 bytes each (excluding the header length).

Fragment offset value for

1st fragment - 0 (No bytes ahead of it)

2nd fragment - 10 (80 bytes of data ahead of it. 80/8=10)

3rd fragment - 20

4th fragment - 30

Options

These contain optional headers and metadata. For example, they may be:

Record Route

Tells the nodes to record the route this packet has taken in the header. Can record upto 9 router addresses.

Source routing

The source defines the route that the packet will take.

It is of two types.

- Strict - The source defines the exact specific nodes the packet will travel through to get to its destination. Each router mentioned in the list must be visited, and routers that are absent in the list must not be visited.

- Loose - The source defines only loose requirements. Routers in the list must be visited, but the packet can also visit other routers.

Users cannot set source routing, only routers are allowed to do this.

Padding

This is added in case the header size is not in multiple of 4.

We need to store the header length in HLEN, which uses a factor of 4.

So, if the header length is 21, we will add 3 bytes of padding to make it 24. Then HLEN will store 24/4 = 6.

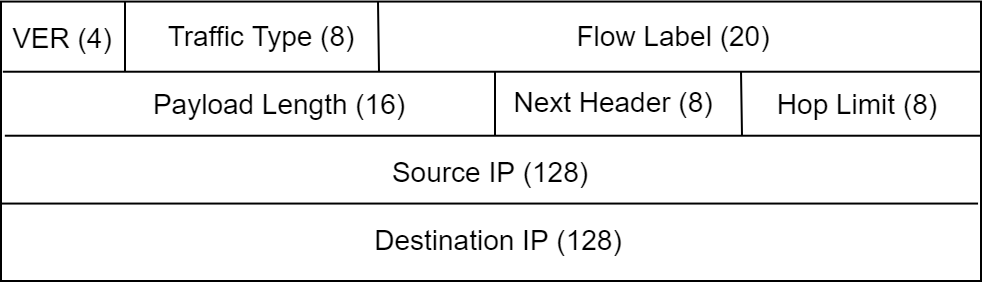

IPv6 Header

- IPv6 uses 128-bit IP addresses instead of 32-bit.

- Only source can fragment packets. Intermediate nodes cannot.

- Header length is fixed at 40 bytes.

VER is the same as in IPv4.

Traffic Type is the same as Type of Service in IPv4.

Flow Label

20-bit value.

For continuous data that travels in a flow, such as video streaming, or live updates, we use flow labels. Even large files may be sent using flows.

Intermediate routers use source IP, destination IP and flow label to distinguish one flow from another. A source and a destination may have multiple flows occurring between them.

For e.g, if you’re downloading two files together from Google Drive, they may be sent through 2 different flows.

So, we give them different flow labels to help identify which flow is which.

Payload Length

Length of the payload

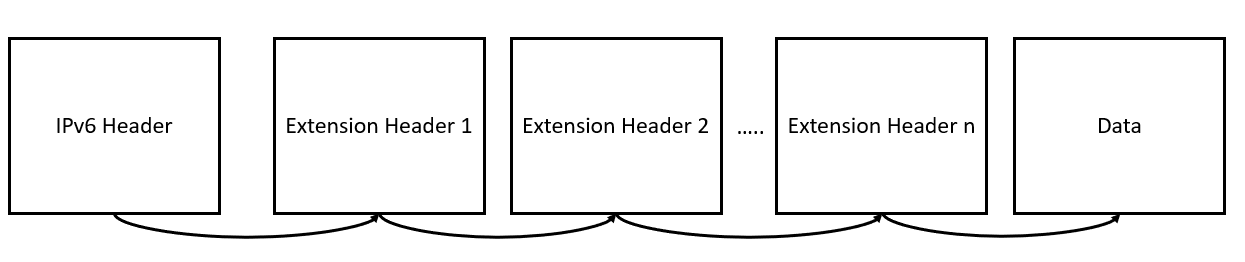

Next Header

IPv6 uses extension headers instead of options. Metadata for routing, authentication, fragmentation, etc. are set in special extension headers.

This field is a 8-bit field that contains the type of the extension header (if present), that comes immediately after the IPv6 header. Each extension header contains its own “Next Header” field. The extension headers are thus chained together like this.

In some cases, this field is also used to indicate protocols in upper layers, such as TCP or UDP.

Hop Limit

Same as TTL in IPv4 Header

Source IP and Destination IP are 128-bit IPv6 addresses for the source and destination respectively.

Extension Headers

Extension headers may be used for many purposes. Some common extension headers used in IPv6 are:

- Routing headers, used if source wants to determine the route the packet should take.

- Authentication headers, used for security purposes.

- Fragmentation Header, used for fragments.

- Destination options - For data that we want only the destination to open, no intermediate routers

- Hop by Hop options, used to specify delivery parameters at each hop on the path to the destination.

Congestion Control

Congestion Control deals with preventing the entire network from having too much data transmitting at once. Even if every single node is transmitting within their individual limits, the combined flow of data may congest the network.

Two main algorithms for Congestion Control are used - Leaky Bucket and Token Bucket.

Leaky Bucket

This algorithm simulates a leaky bucket, which is usually implemented as a queue. The bucket has an incoming stream of water (data) that can have different speeds. There is a hole in the bottom of the bucket that is our output stream, which “leaks” water at a constant rate, even if the incoming stream is faster than it.

This ensures that even if the host is sending a lot of data together, the network is not congested with it. It is usually implemented as a FIFO queue with a fixed output rate.

If the bucket/queue is full, and more data arrives from the host, it will “overflow”,i.e, be lost.

A drawback is that this fixes a rigid pattern at the output, no matter what the pattern of the input is. This is fixed by the token bucket approach.

Token Bucket

In this, tokens are added to the bucket at a constant rate. When a packet arrives, it takes the corresponding amount of tokens in the bucket, and is transmitted. For example, to transmit 1MB data, we need 1MB of tokens.

If the bucket doesn’t have 1MB of tokens, the packet must wait, or be discarded. If the bucket has >= 1MB of tokens, the packet will take as many as it needs (1MB), and be transmitted.

If the bucket is full, no more tokens are added (i.e, incoming tokens are discarded.)

Routing Protocols

Routing Protocols are used to decide the route a particular packet will take to its destination.

Distance Vector Routing (DVR)

- Each node maintains table of minimum distance to every other node in the network.

- Table also contains next entry for each node. I.e, if we have node A’s table, that contains data about node B,C,D… etc. If next value for B is C, that means to get to B from A, we go through node C.

- Information is shared only between neighbors (directly connected). Each node will share its routing table to its immediate neighbours.

- Update may be periodic or triggered.

- Count to Infinity problem may occur in this.

- Three nodes - X—A—B. X-A = 1, A-B=1, X-A=2

- If link between X and A breaks, then the following problem will occur. A will set its distance to X as infinity.

- B will send its routing table to A. A will think B has found another path to X with cost 2. It will update its routing table so that X-A=2+1=3

- A will send new table to B. B will think the cost to get to X (through A) has increased to 3. It will update its table so that X-B=4.

- Similarly, B will again send the new table to A. A will update the X-A value to 5. This process will continue forever.

- Split Horizon technique is used to solve count to

infinity.

- If B knows optimum route to X is through A, it will not send X-B value to A.

- Taking information from A, and sending it back to A, is what causes the loop.’

- A will update the X-A value to infinity. B will send the routing table to A (but without the X-B) value. A will not update anything and send the new routing table to B. B will change the X-B value to infinity.

- Bellman Ford is used to calculate distance tables.

Link State Routing

- Router sends information about its neighbors to the entire network through flooding.

- Uses Dijsktra to calculate routing tables.

- Hello messages are sent to discover neighbor nodes.

Routing in Subnets

When a data packet arrives at a network that has subnets:

- The router will perform bitwise AND of the destination IP in the packet, with all the subnet masks in the network.

- The result of the AND operation will be checked in the routing table.

- In case we find a single match in the table, we will send that packet to the corresponding interface.

- In case we find more than one match, we will send it to the interface with the longest subnet mask

- In case we don’t find any match, we send it to the default interface.

- In fixed length subnetting all subnets have the same mask, so we perform bitwise AND only once.

Network Protocols

ARP (Address Resolution Protocol)

- Each device (computer, phone, printer,etc.) on a network has an IP Address as well as a MAC Address.

- The IP Address identifies the device on the network. The MAC Address is the physical address of the device.

ARP maps a device’s IP Addresses (Logical Address) to its MAC Address.

RARP (Reverse Address Resolution Protocol) maps MAC Address

- If A wants to send a packet to B that is on the same network, it needs the link-layer address (physical or MAC address) in order to send it over the link.

- A will only know B’s IP address, not MAC address. It sends an ARP request.

- ARP request is a broadcast that is sent to all devices on the

network. The request contains

- A’s IP address

- A’s MAC address

- B’s IP address

- The ARP request will be ignored by all nodes except B. B will recognize it’s IP address in the request and it will send an ARP response packet back to A. The response packet will contain B’s IP and MAC addresses. The response packet will be sent only to A, as a unicast.

NAT (Network Address Translation)

- Translates Public IP to Private IP, and vice-versa.

- Due to lack of IPv4 addresses, we separated an organization’s public IP from its private IP.

For e.g, an organization has 100 different computers, that all need to connect to the Internet. Instead of giving them 100 public IPs, we give the organization a single public IP.

Each of the 100 hosts is then given a private IP.

For example:

Organization’s Public IP - 192.20.20.0

Private IPs in the Organization - 10.0.0.1, 10.0.0.2, 10.0.03, etc.

We attach a NAT (Network Address Translator) to the organization’s network. Generally this is part of the router.

NAT translators will translate a private IP to a public IP, so that the computer can access the Internet, or other networks. It can send data to the Internet, and receive data from the Internet.

When sending data, the NAT will translate private IP to public IP. When receiving data, it will translate public to private IP. Different port numbers may be used to identify different computers.

Transport Layer

Responsibilities

-

Port to Port Delivery/ Process to Process Delivery. It must deliver the data from the sender application (for e.g, a browser) to the receiver application (the server of the website the user opened).

-

Segmentation - Break down the data into smaller parts that can be sent over the network, and reassemble it at the receiver side.

-

Multiplexing and Demultiplexing - A single device generally only has a single connection to the Internet (or any other network). If multiple applications are using that connection, multiplexing and demultiplexing of data is done.

-

Connection Management

-

Reliability - All the data must be delivered to the receiver correctly. No lost/corrupted data should be delivered. Lost/corrupted data must be detected and resent. UDP doesn’t provide reliability.

-

Order - Data must be sent in order. If the data was broken down into 4 parts, they must arrive in the correct order.

It is possible that the network layer sends them out of order - for e.g, 2,3,1,4. The Transport layer must correct the order before delivering the complete data to the Application Layer. UDP doesn’t provide in-order delivery.

-

Error Control - Checksums are used for this. Receiver verifies the checksum that the sender sent.

-

Congestion Control

-

Flow Control

Socket Address and Port Numbers

Socket Addresses are made up of an IP address, and a 16-bit port number. They are used to uniquely identify a TCP/UDP/ any other transport layer protocol connection.

A particular computer will have an IP address, but many applications running on it may need to access the Internet. When data packets arrive, the OS must be able to figure out which data packet belongs to which application.

A unique port number is assigned to each application. Only one application may use a particular port at a given time. For e.g, two applications cannot listen on port 3000 at the same time.

Port Number Types

There are three categories of port numbers:

-

Well Known/System Ports - These are the ports for most commonly used networking tasks. For example, a web-server will always listen for HTTP requests on Port 80, and HTTPS on port 443. An email server will always listen on port 25 for SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) requests. Assigning fixed numbers makes it easier to handle common tasks. Typing www.google.com in a browser is the same as typing www.google.com:443, because the browser knows that the standard port for HTTPS is 443.

Range for these is 0-1023.

-

Registered/User Ports - Organizations and Applications can have specific ports reserved for their use. They can register these with IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority). For e.g, Xbox Live has 3074 port number reserved for it.

Range for these is 1025-49151.

-

Dynamic/Ephemeral Ports - These are the rest of the ports left in the range. When an application needs to use a transport layer protocol, it requires a port number. The OS will generally assign it any random port number that is currently not in use.

Range for these is 49152-65535

Registered, and even well-known ports can be used for other tasks. For example, you can still run an email server on Port 80. You can also use Port 3074 for something other than Xbox Live. These are simply guidelines and standards to prevent confusion and clashes.

IP Address is used to differentiate one machine from another. Port Numbers are used to differentiate different applications on the same machine.

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is a popular transport layer protocol. Most applications, such as HTTP, HTTPS, Email (SMTP/IMAP), etc. use TCP.

Characteristics

Characteristics of TCP are:

- Byte Streaming - Application layer continuously sends data to the transport layer. TCP breaks it down into bytes, and packages several bytes into a single segment. Multiple segments are created and sent to the receiver.

- Connection-Oriented - TCP establishes a connection with the receiver first, using a 3-way handshake. All future communication between sender and receiver occurs over this connection.

- Full Duplex - Two-way communication can happen, at the same time.

- Piggybacking - Sender sends data to receiver, and

receiver must send back acknowledgement for that data. In most cases

these days, communication occurs both ways, i.e, if A sends data to B, B

also sends data to A. Thus, instead of B sending acknowledgements

separately to A, B will attach the acknowledgement along with the data

it has to send A.

- Needs buffers - Sending and receiving processes may not operate at same speed, therefore TCP needs sender and receiver buffers for storage.

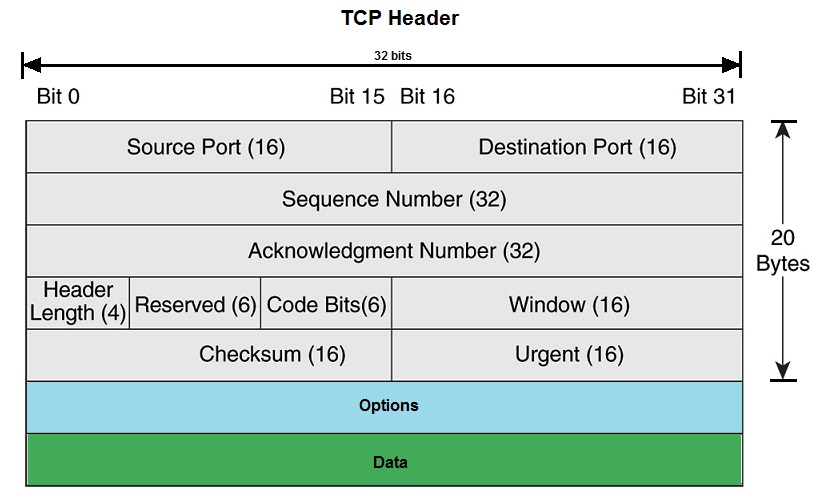

TCP Header

TCP Header is attached to each TCP Segment. It contains the following fields. It’s size can vary from 20-60 bytes.

Source Port

Port Number for the source (sender) application.

Destination Port

Port Number for the destination (receiver) application.

Sequence Number

Each segment is given a sequence number based on the data sent before it. When a TCP connection is established, a random sequence number is generated.

For e.g, let the initial sequence number be 500. (For now, ignore the increase in sequence number during the 3-way handshake)

Let’s say A sends B 200 bytes of data, in 4 segments of size 50 bytes. The sequence number will be 500 for the first segment, 550 for the second segment, 600 for the third, and so on.

Acknowledgment Number

This is used to let the sender know that the packet that it sent has been received. It is set as the value of the next sequence number that the receiver is expecting.

For e.g, if A sends B data with sequence number 500, that has 50 bytes in it. Thus, B receives bytes number 500,501,502….549. Now, it expects byte number 550. Thus, it will set Acknowledgement Number as 550.

Header Length/Data Offset

Length of the TCP Header. Uses a factor of 4, same as IPv4 Header’s HLEN field

Reserved

Next 6 bits are reserved for future use. 2 of them have already been defined as CWR and ECE.

Code-Bits/Flag Bits

There are 6 Flag Bits, each with their own purpose.

URG (Urgent)

If this bit is set to 1, it means that this segment contains urgent data. Location of the urgent data is set in the urgent pointer.

ACK

Indicates that this message contains an acknowledgement, i.e, the value of the acknowledgement number is significant.

PSH (Push)

When receiver is receiving data, it will generally buffer some amount of data before sending it to the application layer. PSH field indicates that the receiver should stop buffering and push whatever data it has to the application layer.

RST (Reset)

Used to Reset the TCP connection.

SYN (Sync)

Used to sync sequence numbers. Only the first packet sent from each end should have this value set.

FIN (Finish)

Used to terminate the connection.

Window Size

Specifies the size of the receiver’s window, i.e, the current amount of data it is willing to receive. A will tell its window size to B, and B will tell its window size to A.

Checksum

Used for error-checking.

Urgent Field

If the segment contains urgent data, this field tells where the urgent data is located. It contains the sequence number of the last urgent byte. For eg, if A sent bytes number 500-549, and bytes 500-520 are urgent, the urgent field will contain the value 520.

Options

Contains optional fields, such as timestamps, window scale, and maximum segment size (MSS). MSS is the maximum size of one single segment that the receiver is willing to accept. It is separate from window size, which may be larger, as a window can contain multiple segments.

Padding

In case the total header size is not a multiple of 4, we add empty zeroes to make it so, so that we can store it in the header length field.

TCP Connection Establishment

A 3-way handshake is used to establish a TCP connection. This process occurs before any actual data is sent. The 3 steps are:

-

SYN - Sender will send the receiver a connection request. It will send a randomly generated sequence number,its port number, its window size, etc. It will set the SYN flag as 1, indicating that it wants to set up a connection.

Let’s say A sent a connection request to B, with the sequence number 3000 (random), and window size as 1200 bytes. This will let B know that A only can only receive 1200 bytes of data (until it empties its buffer again)

-

SYN-ACK - The receiver will respond to the sender’s request. It will send a response, with SYN field as 1. It will also send an acknowledgement (in the same response), and tell its own window size to the sender.

B will reply to A. It will generate a random sequence number, say 5000. It will set the ACK and SYN flag. It will also set the acknowledgement number to 3001 (since A’s sequence number was 3000.) It sends A its window size, say 800 bytes.

-

ACK - Sender will acknowledge the response. After this, sender and receiver will begin exchanging actual data. SYN flag is 0 in this.

A will send B a response with sequence number 3001, and Acknowledgment number 5001. ACK will be set as 1. SYN flag will be 0.

Sequence numbers are not consumed if PURE ACK is sent. If a segment contains only ACK, and not data, and it uses sequence number \(x\), then the next segment can also use sequence number \(x\).

After this, A and B can start exchanging data. Both A and B will reserve some resources (memory, RAM, etc.) for this A-B TCP connection.

A will not send more than 800 bytes to B, and B will not send more than 1200 bytes to A. A will send sequence numbers 3002,3003,3004…., and B will send sequence numbers 5001,5002,5003… and so on.

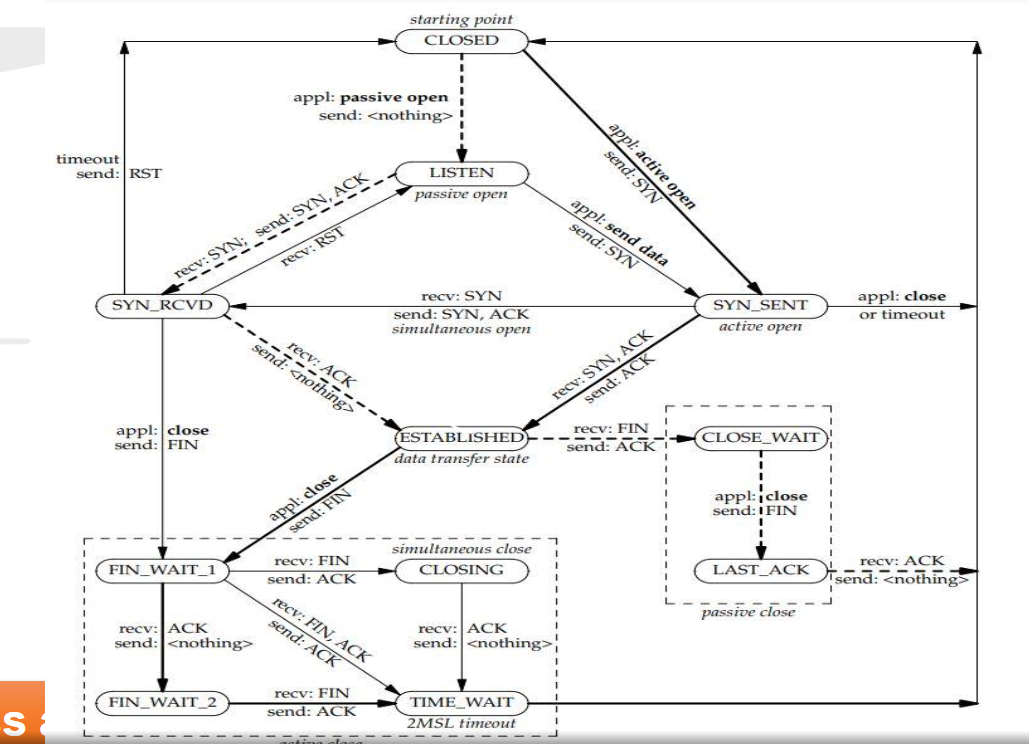

TCP Connection Termination

4-way handshake.

-

FIN from Client- Client wants to close the connection. Client will send server a segment with FIN bit as 1. (Server may also choose to close the connection)

Client will enter FIN_WAIT_1 state. In this state, the client waits for an ACK from the server for this FIN segment. This is also called Active Close state.

-

ACK From Server- Server will receive the FIN segment, and send an ACK to the client. Server now enters a Close Wait (Passive Close) state. Server will release any buffer resources, because client has said it doesn’t want to send any more data to server. (Server may still have data to send to the client).

When the client receives the ACK from server, it enters FIN_WAIT_2 state. In this state, the client is waiting for the server to send a segment with FIN bit set as 1 (i.e, client is waiting for server to also close the connection.)

-

FIN from Server - Server can send any pending data, and then it will send a segment with FIN bit as 1. Server now enters LAST_ACK state. In this state, the server only expects to receive one last ACK from the client (for the FIN segment server just sent). After receiving the ACK, Server will release all resources for this connection, and the connection will be closed.

-

ACK from Client - Client will receive the server’s FIN segment, and send an ACK for it. Client will enter TIME_WAIT state. In this, the client waits in case the final ACK was lost. If the final ACK was lost, the server will timeout and resend the FIN message. If the client receives any FIN message in the TIME_WAIT state, it will resend the ACK. If it doesn’t, client assumes the last ACK was successfully delivered, and it will close the connection.

The amount of time to be waited varies, but it’s generally 30s or 1 min.

Dashed lines are for server, solid for client.

TCP Congestion Control

Congestion Window is used for congestion control. Size of congestion window changes throughout the TCP connection. We first increase it, to send more data in less time. In case congestion occurs while increasing, we again decrease it.

Concept of MSS (Maximum Segment Size) is used.

Congestion Control in TCP has 3 phases:

-

Slow Start Phase (Exponential Growth) - In this, the congestion window is increased exponentially. Initially, the window size is 1 MSS. Then it becomes 2 MSS, then 4, then 8, then 16, and so on, until the slow start threshold. Slow Start Threshold is determined as \[ (Receiver Window Size/MSS)/2 \] This gives max number of segments in slow start phase (not their size.)

-

Congestion Avoidance Phase (Linear Growth) - Congestion Window grows linearly. If it at \(x\) MSS , it becomes \(x+1\), then \(x+2\), and so on.

This continues until congestion window size becomes equal to receiver window size. After that, we keep congestion window size as constant.

-

Congestion Detection - Congestion is detected in this phase, and we change window size to accommodate it.

There are two ways in which congestion can be detected:

-

Time-Out - When timer times out before we receive an ACK. Congestion in this case is Severe.

-

3-ACK- Sender receives 3 duplicate ACKs for the same segment. Congestion in this case is light.

For e.g, if sender sent packets 1,2,3,4 and 5. Receiver received packet 1 and sent ACK 2 (Original ACK). Packet 2 was lost. Receiver received packet 3, and again sent ACK 2 (because it hasn’t received packet 2). Receiver received packet 4, and again sent ACK 2. Similarly for packet 5. Sender will thus receive 4 ACKS - 1 original, and 3 duplicate acknowledgments for packet 2.

-

Reaction in Congestion Detection

Time-Out

- Slow Start Threshold is set as half of current window size. For e.g, if current window size is 16 MSS, slow start threshold will be 8.

- Congestion window is reset to be equal to 1 MSS.

- Slow Start Phase is resumed

3-ACK

- Slow Start Threshold is set as half of current window size.

- Congestion window is set equal to slow start threshold

- Congestion Avoidance phase is resumed

Wrap-Around

- TCP Sequence numbers go from 0 to \(2^{32}\) .

- This doesn’t mean only 4GB (\(2^{32}\) bytes) of data can be sent

- After all the sequence numbers are used, and more data needs to be sent, sequence numbers can be wrapped around and used from starting

- Time taken to use all the \(2^{32}\) numbers is called wrap around time

Wrap Around Time = \(\frac{2^{32}}{bandwidth}\)

Life Time of a TCP Segment is 3 minutes or 180 seconds, i.e, a receiver will have to wait max 3 minutes before it receives a segment

- if WAT > LT, no issue

- if LT> WAT, then receiver can receive multiple segments with same sequence number. To solve this, additional fields like timestamp are used.

TCP Window Scaling

-

TCP Window Size field is 16-bit, which means the window can only be \(2^{16}\) bits, or 64KB.

-

This is generally too less for modern applications

-

Using the options headers in TCP, we can specify a scaling factor. For e.g, if scaling factor is 3, and the window size is specified as 400, then the actual window size will be \(400*2^3 = 3200\).

i.e, \[ WS_{real} = WS_{field\_value}*2^{scale\_factor}\]

-

Generally, this is allowed when the bandwidth delay product is greater than 64KB.

Bandwidth Delay Product = Bandwidth * RTT

-

Maximum value of scaling factor is 14, i.e, the max window size becomes \(2^{16} * 2^{14} = 2^{30} = 1GB\)

Sender Window in TCP is calculated using both Receiver Window Size and Congestion Window Size. It is chosen as the minimum of both. Sender window size being larger than either of those will result in TCP retransmission.

TCP Timers

Retransmission Timer

- TCP start timer after each transmission. If an ACK is not received before this timer runs out, the segment is retransmitted.

- The amount of time it waits is called RTO (Retransmission Timeout)

- RTO is calculated using RTT, there are many ways to do so.

Measured RTT (\(RTT_m\))

This is the direct measured value of how long it takes for a packet being sent and for its ACK to be received.

Smoothed RTT (\(RTT_s\))

It is the weighted average of measured RTT, since \(RTT_m\) can fluctuate.

It is calculated as:

After the first measurement, \(RTT_s = RTT_m\)

After each measurement, \(RTT_s = (1-t)*RTT_s + t*RTT_m\)

where \(t=1/8\) , unless specified. \(t\) is also sometimes written as \(\alpha\)

RTO can be then kept as \(2*RTT_s\)

Deviated RTT (\(RTT_d\))

It is calculated as:

After the first measurement, \(RTT_d = RTT_m/2\)

After each measurement, \(RTT_s = (1-k)*RTT_s + k*(RTT_m-RTT_s)\)

where \(k=1/4\) , unless specified. \(k\) is also sometimes written as \(\beta\)

RTO is then calculated as \(RTT_s+4*RTT_d\)

Time-Wait Timer

- Takes care of late packets

- Never close a TCP connection immediately. Wait for 2*LT, so that any delayed packets can arrive.

Keep-Alive Timer

- Used to close idle connections.

- Periodically check connections, and close them if no reply.

- After keep-alive time duration, server will send 10 probe messages with gap of 75 seconds. If no reply, the connection is closed.

- Keep-alive time duration is generally 2 hours.

Persistent Timer

- Suppose receiver’s buffer is full, so it sends an ACK to sender with window-size=0

- Sender understands that it cannot send more data as receiver buffer is full, and it waits.

- Receiver processes the data in buffer and empties it. Now it has space, so it sends another ACK to server with window-size = some non-zero value. Suppose this ACK gets lost.

- Now, sender is waiting for receiver to empty its buffer, and receiver is waiting for sender to send data. This is a deadlock.

- To prevent this, persistent timer is use. When sender receives a packet with window size=0, it will start a persistent timer.

- After that timer goes off, it will send a probe with only 1 byte of new data. The receiver will receive this probe and send its new window size.

- If the new window size is non-zero, the sender will start transmitting data. If it is still zero, the sender will start the persistent timer again and wait.

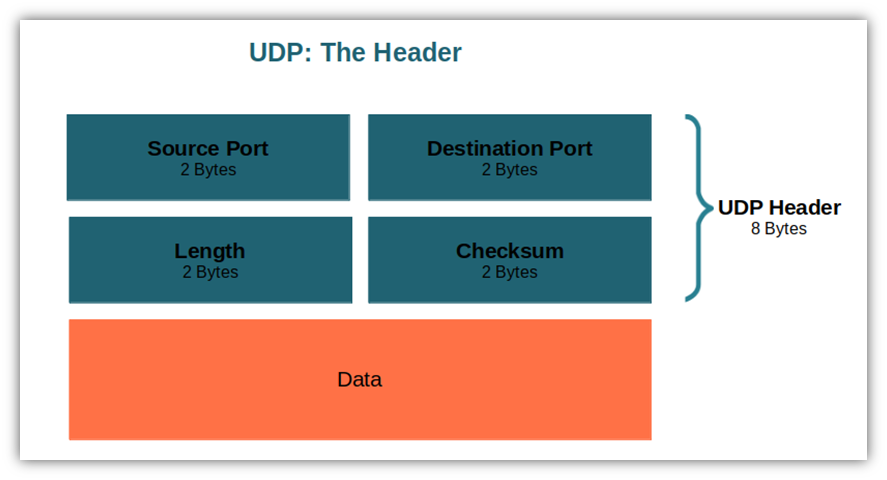

UDP

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is another transport layer service. It’s popular applications include DNS, VoIP, etc.

Characteristics

- Connectionless

- Unreliable

- Messages may be delivered out of order.

- Less overhead, as header is very small.

- Faster than TCP.

Header

- Header size is fixed at 8 bytes.

- Length contains total length (header+data)

- Maximum length of UDP datagram is \(2^{16}\) bytes (including header)

- Checksum field is optional in IPv4, mandatory in IPv6.

UDP Applications

- Query-Response Protocol (One query-One reply, no need to make a connection as we only need one reply). For e.g - DNS

- Speed - When we need high-speed applications. For e.g. - Online games, VoIP.

- Broadcasting/Multicasting- Eg, RIP (Routing Information Protocol), Distance Vector Routing. Nodes share routing tables after every 30 seconds, to all other nodes. If we use TCP, the node will have to establish connections with all other nodes, which will be time consuming.

- Continuous Streaming- E.g, Skype/YouTube.

- Stateless - Don’t save information about the connecting clients.

TCP vs UDP

| TCP | UDP |

|---|---|

| Connection-Oriented | Connectionless |

| Reliable | Unreliable |

| In-order Delivery | Delivery may be out of order |

| Error Control is Mandatory | Error control is optional |

| Slow | Fast |

| More Overhead | Less overhead |

| Flow Control, Congestion Control | No flow control or congestion control |

| HTTP, FTP | DNS,BOOTP,DHCP |

Application Layer

Enables users (human or s/w) to access the network. It is responsible for providing services to the user.

Paradigms

- Provides services to the user

- To use the internet we need 2 application programs that communicate with each other using the application layer.

- Communication uses a logical connection, i.e, the 2 application programs assume that there is an imaginary direct connection between them. In reality, the communication happens through various layers (Transport, Network, Data-Link, etc.)

There are 2 types:

- Client-Server - Server program provides service to the client program. It is the most popular method today. Server runs continuously. Client creates a connection to the server using the Internet and requests a particular service.

- Peer to Peer - Gaining popularity in recent times. Both communicating programs have equal responsibility and power. No program needs to be always running. A computer can even provide and receive services at the same time.

File Transferring

FTP (File Transfer Protocol)

- It’s an application layer protocol used for transferring (uploading and downloading) files over the Internet.

- It uses TCP under the hood.

- It solves problems such as different systems having different ways of representing and storing files.

- It establishes 2 connections between 2 hosts:

- One connection is used for control information (commands and responses). This uses TCP port 21. It remains active during the FTP session.

- The other connection is used for actual data transfer. This uses TCP port 20. It closes and opens for each file transfer.

Security in FTP

- Security was not a big issue when FTP was created.

- FTP supports passwords, but they are sent unencrypted, therefore they can be intercepted.

- Data is also transferred unencrypted.

- SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) can be added to FTP (between FTP and TCP) to make it more secure. This makes it SSL-FTP.

FTAM (File Transfer Access Management)

- FTP was created by the Internet standard. FTAM is the OSI counterpart to FTP.

- It is a Application Layer protocol that provides access and management to a distributed network file system.

- It allows users to access file systems both locally and remotely.

- It defines an architecture for a hierarchical file system. Any file system that wants to be accessible using FTAM must follow this architecture.

- It does not define or create a user interface for accessing such file systems. Vendors and users can create their own based on the architecture specified.

- It is more similar to Gopher or WWW rather than FTP. FTP only allows files, whereas FTAM also allows links to other FTAM directories (like WWW does)

- Used to send messages over the Internet

- Used to be plain text, now can include images, videos, files, etc.

- Actual message transfer is done using a message transfer agent (MTA). Client must have client MTA to send mail, server must have server MTA to receive mail.

SMTP

SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) is the formal protocol that defines MTA client and server applications. SMTP defines how commands and responses must be sent back and forth. It is used twice, once between sender and sender’s mail server, and second between sender’s mail server and receiver’s mail server. Mail is transferred in 3 phases - Connection Establishment, Mail Transfer, and Connection Termination.

Components of SMTP

Mail User Agent (MUA)